Cradle to Table: Reclaiming Food Traditions in the First 1,000 Days to Prevent Diabetes.

How Early Nutrition Shapes Lifelong Metabolic Health and Fights the Rise of Childhood Diabetes

While much of the conversation centers on curing diabetes, true prevention begins long before symptoms appear—in the womb, at the breast, and within the first 1,000 days that shape a child’s future health.

In our last edition, we discussed the impact of paternal alcohol consumption at the time of conception and its potential effects on child health. In this edition, we shift our focus to the first 1,000 days of life—from conception to a child’s second birthday—and examine how this time period offers unique opportunities for preventing chronic diseases, with a particular emphasis on diabetes.

The First 1,000 Days: A Critical Window for Preventing Diabetes.

A child’s first 1,000 days—from conception to their second birthday—forms the basis for lifelong health. During this window, the brain, immune system, metabolism, and organs are especially sensitive to early exposures, including nutrition. While isolating the specific impact of nutrition on metabolism and chronic disease is inherently complex, new research by Gracner et al., published in Science, offers valuable insights. Leveraging historical data from sugar rationing associated with World War 2, the study found that UK adults who spent their first two years of life (including gestation) under sugar rationing had significantly better health decades later. Specifically, they showed a 35% lower risk of type 2 diabetes and a 20% lower risk of high blood pressure in midlife.

One-third of this health benefit came just from being in a lower-sugar environment while in the womb. This speaks volume on the importance of maternal diet.

Cravings are real, but can be satisfied in healthy way, too !

Outside the womb, the traditional journey of nourishment for the infant begins with colostrum and breast milk. But, the modern feeding practices of bottle feeding and baby formula introduces added sugars early on. Despite the growing evidence of the risks, many commercial infant foods still contain added sugars. And, there are no formal sugar intake guidelines for children under age four, even though experts recommend avoiding sugar-sweetened drinks and ultra-processed snacks altogether.

Complementary feeding, which typically begins around six months of age, is a critical phase in a child’s nutritional development. This period—commonly referred to as weaning—should emphasize nutrient-dense, minimally processed foods such as mashed vegetables, lentils, fruits, and small portions of iron-rich animal foods. WHO and UNICEF recommend continued breastfeeding alongside appropriate complementary feeding until age two and beyond. However, ultra-processed, sugar-laden foods are often marketed as toddler snacks, contributing to poor metabolic programming in early life.

While improving food literacy is important, real impact requires holding the food industry accountable: reformulating baby foods, regulating deceptive marketing, and specifically subsidizing access to nourishing options grounded in Indigenous food systems.

Breast-feeding offers lasting health benefits for both mothers and children. A WHO meta-analysis of 39 studies found breast-fed individuals were less likely to become overweight or obese. Accordingly, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusive breast-feeding for the first six months, with continued breast-feeding for at least a year. Yet, despite high initiation rates in the U.S., fewer than 20% of mothers maintain exclusive breast-feeding at six months. Narrowing this gap could yield significant health benefits.

It's protective effects are well-documented in high-income settings, but results are mixed for infants of diabetic mothers. Prospective studies are needed to understand how early lactation interacts with maternal metabolic conditions and postnatal behaviours. Colostrum, rich in bioactive compounds, illustrates why early initiation is especially critical, particularly in preventing neonatal hypoglycemia among infants of diabetic mothers. Additionally, breast-feeding is linked to a 24–32% lower risk of type 2 diabetes and modest reductions in type 1 diabetes.

Barriers to breast-feeding are more pronounced in rural and Indigenous communities. These include limited access to support, culturally unsafe care, and disrupted intergenerational knowledge due to colonial policies like residential schools. Although national breast-feeding initiation rates are high, they remain significantly lower among First Nations mothers. Studies show that culturally tailored education can positively shift attitudes and normalize breast-feeding among Indigenous youth, rebuilding supportive norms across generations.

If we specifically discuss diabetes as one of the indicator for nutrition, Type-1 and Type-2 Diabetes remain a prevalent health challenge in society, particularly in Indigenous communities. According to Diabetes Canada, as of March 2025, Type-1 and Type-2 Diabetes affect:

17.2% of First Nations individuals living on-reserve

12.7% of First Nations individuals living off-reserve

4.7% of Inuit people

9.9% of Métis people

5.0% of the general population

The age of onset of diabetes in the indigenous population is much lower than that of the general population. It was also noted that within the same community, women had a higher prevalence of diabetes when compared to men, after the age of 30. This is in contrast with what is seen in the general population of Canada, in which there is a male predominance of diabetes.

The Three Silent Drivers

Focussing on Diabetes, three factors which initiate diabetes in children are:

Sugar exposure in infancy

Gestational diabetes

Intergenerational Risk Loops

Sugar exposure in Infancy

As discussed before, a growing body of evidence indicates that the maternal glycemic environment during pregnancy has profound, long-term consequences for offspring health. Diets with a high glycemic index or load accelerate trans-placental glucose transfer, thereby altering fetal growth trajectories and body composition. These effects are amplified in women who enter pregnancy overweight or obese, a group already predisposed to insulin resistance and sub-optimal glucose metabolism.

Gestational diabetes and congenital outcomes

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) now affects roughly 14 % of pregnancies worldwide. It arises from the combined effect of heightened insulin resistance and insufficient β-cell compensation. Importantly, GDM is not a transient problem confined to pregnancy:

Children born to mothers with GDM have a markedly higher risk of childhood obesity and early-onset type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Among mothers with pre-existing T2D, congenital malformations occur at 40.5 per 1,000 live births, almost double the English population baseline of 21.3 per 1,000 (Murphy et al.).

Intergenerational risk loops

Hyperglycaemia in pregnancy sets off a self-perpetuating “risk loop.” Elevated maternal glucose initiates the fetus for adiposity and reduced insulin sensitivity. If the child subsequently grows up amid:

limited access to nutritious foods,

chronic stress or trauma,

ubiquitous, ultra-processed diets, and

culturally unsafe healthcare,

The probability of developing obesity or T2D in childhood rises sharply—leading, in turn, to higher-risk pregnancies in the next generation.

Structural amplifiers in Indigenous settings

For many Indigenous families, these risks are compounded by historical and ongoing social determinants: land displacement, disrupted food systems, intergenerational trauma, and under-resourced prenatal care. As a result, metabolic risk is not just biological but deeply intertwined with colonial and structural inequities.

Breast-feeding poses challenges for many new mothers, but those living in rural areas face distinct barriers. A University of Missouri study underscores how limited access to support services and reliable information—such as lactation consultants, peer networks, and practical guidance—can leave rural mothers feeling unprepared and overwhelmed.

Recent data illustrate the disparity: while Health Canada reports that roughly 87 % of mothers nationwide initiate breast-feeding, initiation and continuation rates in many First Nations communities lag behind.

Encouragingly, targeted education can help close this gap. In Martens’s study of youth-oriented interventions, First Nations adolescent girls showed markedly stronger beliefs in breast-feeding and weaker beliefs in bottle-feeding after completing a culturally tailored program. Participants also reported feeling less self-conscious about breast-feeding in public and more likely to support others who choose to breast-feed—highlighting the potential of early, culturally safe education to rebuild breast-feeding norms across generations.

Disproportionate burden in First Nations communities

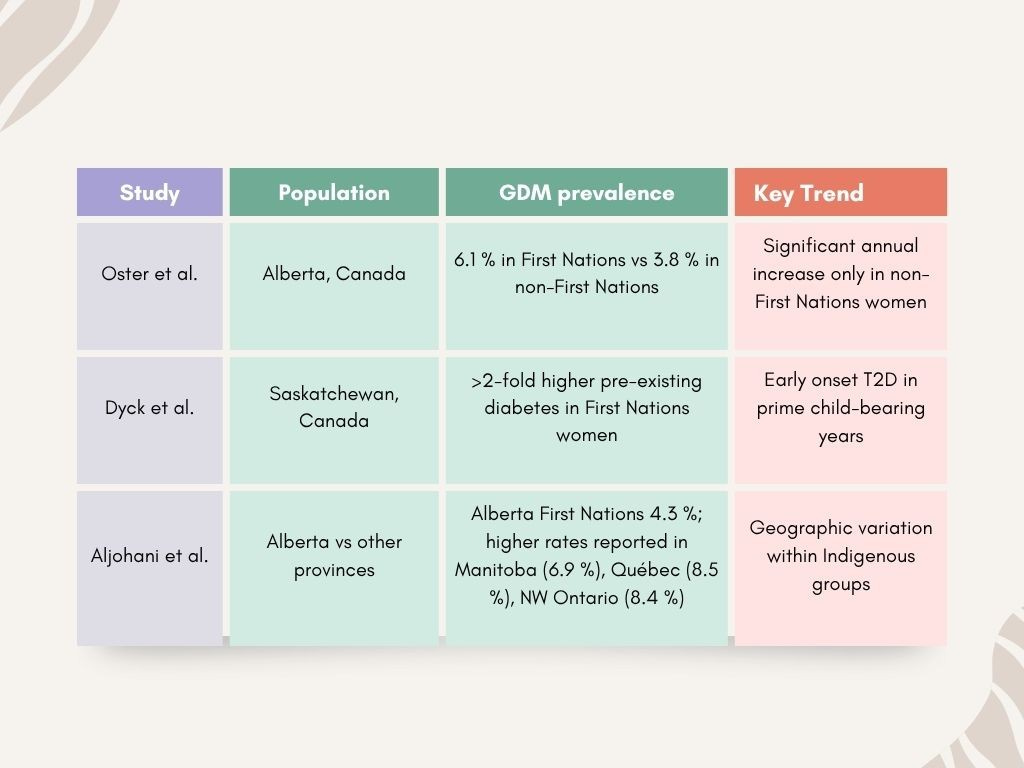

Epidemiological data show a consistently higher burden of hyper-glycaemic pregnancy in Indigenous populations:

These figures underline a double metabolic load: higher background type 2 diabetes prevalence and heightened GDM risk during pregnancy.

The Persistence of the “Thrifty Gene” Narrative in Canadian Health Care

The “thrifty gene” theory—proposed in 1962 by geneticist James V. Neel to explain high diabetes rates among Indigenous peoples—suggested that genetic adaptations to historical food scarcity became harmful in modern environments. Though Neel later retracted the idea, the theory continued to influence Canadian health policy, often reinforcing racialized assumptions.

Despite advances in genomics, Indigenous populations remain underrepresented in major databases like gnomAD. This exclusion, combined with concerns about cultural harm, exploitation, and data misuse, highlights the need for ethical, community-led research. A truly inclusive approach must center Indigenous voices, respect cultural values, and involve communities at every stage—from design to governance.

Brief Vignettes of Successful Early-Life Interventions

Antenatal Nutrition Bundles and Diabetes Screening : In several Indigenous communities, integrating antenatal nutrition education with routine screening for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) has shown promising results. For instance, a program in northern Manitoba combined culturally adapted nutrition counselling with early GDM screening and follow-up. This initiative led to improved dietary quality among pregnant women and early identification of GDM, enabling timely intervention to prevent complications for both mother and infant (Heaman et al., 2018). The use of “nutrition bundles”—which include iron, folic acid, and vitamin D supplements alongside education—has been endorsed by programs like the Canada Prenatal Nutrition Program (CPNP), especially in high-risk populations (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2015).

Community-Based Breastfeeding Support Programs Community-led breastfeeding promotion efforts have had significant success when grounded in local values and traditions. For example, the Breastfeeding Education Support and Training (BEST) initiative in British Columbia provided peer support networks and culturally safe lactation consulting services. This contributed to a marked increase in exclusive breastfeeding rates at 6 months among Indigenous participants (Martens, 2012). By addressing barriers such as isolation, limited access to lactation consultants, and generational trauma, these programs rebuild community confidence in traditional infant feeding practices.

First-Food Education Rooted in Traditional Practices Programs that reconnect families with traditional "first foods" (e.g., wild game, berries, and traditional broths) as part of early weaning education have shown not only improved nutrition but also strengthened cultural identity. In the Yukon Territory, the Honouring Our Food project delivered hands-on workshops led by Elders and nutritionists, which significantly increased parental knowledge of local, healthy weaning foods and reduced reliance on processed alternatives (Kenny et al., 2014). This approach respects Indigenous food systems and reinforces the role of ancestral knowledge in public health.

Home-Visiting Programs Tracking Infant Weight and Nutrition Home-visiting programs such as Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities (AHSUNC) include regular monitoring of infant growth, nutrition counselling, and caregiver support. These visits, conducted by trusted community health workers, have been linked with earlier detection of growth faltering and improved maternal engagement in nutritional practices (Greenwood et al., 2015). The integration of developmental tracking and culturally relevant guidance helps families stay on track during the critical first 1,000 days.

Our journey from 'Cradle to Table' highlights a critical window of opportunity to reshape the future of diabetes.

By investing in nurturing environments, supporting traditional foodways, and challenging industrial food systems, we can break the cycle of chronic disease. The following graph, based on data from Statistics Canada, visually encapsulates the current reality of diabetes prevalence across Canadian age groups, serving as a powerful testament to why our focus on early life prevention is paramount."

Older Adults Bear the Highest Burden

Among all age groups, people aged 65 and over consistently have the highest rates of diabetes. Their prevalence sits between roughly 17.5% and 19.5%, peaking around 2019 at nearly 19.5%. Although there was a slight dip in 2021, rates nudged back up in 2022, remaining quite high overall.

Why Are Older Adults More Affected?

The much higher prevalence of diabetes among those aged 65 and over and 50 to 64 years likely reflects the long-term effects of lifestyle and dietary habits. Type 2 diabetes doesn’t develop overnight; it often results from years of insulin resistance building up. This means that decades of eating patterns—like diets high in refined carbs, sugars, and unhealthy fats—combined with less physical activity, gradually increase the risk of developing diabetes later in life.

The next most affected group is those aged 50 to 64 years, with rates generally ranging from 9.5% to 11.5%. This group saw a small rise from 2015 to 2017, a peak in 2019, a slight drop in 2020, and then a recovery by 2022 reaching their highest point again.

Diabetes is much less common in younger age brackets. For example, the 18 to 34 years group stays consistently below 1.5%, with only a small bump around 2017. The 12 to 17 years group shows the lowest prevalence — well under 1% across all years — though there was a tiny increase in 2022 that’s worth keeping an eye on.

What’s Behind the Slight Rise in Younger People?

Though still low, the small increase in diabetes rates seen in the 12 to 17 and 18 to 34 age groups in 2022 raises some flags. From a nutritional standpoint, this could be linked to rising childhood obesity rates, more sedentary lifestyles, and greater consumption of ultra-processed foods and sugary beverages. These factors are known to contribute to early insulin resistance, putting younger generations at risk for developing Type 2 diabetes much earlier than previous generations.

Middle-aged adults (35 to 49 years) fall somewhere in between, with rates generally hovering between 3.5% and 4.5%. Their prevalence dipped a bit early in the period, then rose in 2019, dipped again in 2020, and climbed slightly in the last couple of years.

Looking at the big picture, diabetes rates across all age groups have remained relatively steady over these eight years. There haven’t been any dramatic jumps or drops, suggesting no major diabetes outbreaks or revolutionary treatments that changed the landscape drastically during this time.

That said, the older age groups (50–64 and 65+) have shown a slight upward trend in recent years, and even the youngest group (12–17) has a small uptick in 2022. While these aren’t alarming yet, they’re signals worth monitoring closely moving forward.

A Few Important Notes

Type of Diabetes? The data doesn’t break down types, but given the age patterns, it likely mostly reflects Type 2 diabetes, which is more common in older adults.

What’s Driving These Trends? This analysis only looks at how common diabetes is, not the reasons behind it. Factors like lifestyle, genetics, healthcare access, and public health initiatives all play a role but aren’t visible here.

Data Quality: The smoothness of the trends suggests consistent data collection methods.

The overall stable prevalence rates between 2015 and 2022 might suggest that, on a population level, dietary habits haven’t changed drastically enough to cause big shifts in diabetes rates during this time. However, this doesn’t mean diet isn’t an ongoing underlying factor. Individual food choices, lifestyle, and environmental influences continue to quietly shape diabetes risk year after year.